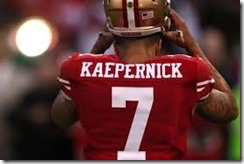

Recently Colin Kaepernick has made a visible attempt to express his own evaluation of his person and his place in American society. Colin Kaepernick is black, and as a black American he is choosing to remain quietly seated or down on one knee when the national flag is displayed at the beginning of football games. This has engendered much discussion and much reaction, ranging from applause to opposition to outright hatred that “he is not respecting the flag and our nation’s military.” Some of his football peers have chimed in, some to say that such protest is not needed. Some have not commented. Some have supported him in words, and some have emulated him in action. You can find examples of reactions and choose which players you support, I guess, using them as a club against Kaepernick and his actions.

Recently Colin Kaepernick has made a visible attempt to express his own evaluation of his person and his place in American society. Colin Kaepernick is black, and as a black American he is choosing to remain quietly seated or down on one knee when the national flag is displayed at the beginning of football games. This has engendered much discussion and much reaction, ranging from applause to opposition to outright hatred that “he is not respecting the flag and our nation’s military.” Some of his football peers have chimed in, some to say that such protest is not needed. Some have not commented. Some have supported him in words, and some have emulated him in action. You can find examples of reactions and choose which players you support, I guess, using them as a club against Kaepernick and his actions.

But specifically, the reaction to Kaepernick seems to center around “protest” and how that is disruptive at certain times and places. “Surely you won’t protest the flag ceremony on 9/11, the most sacred and solemn day of national remembrance!” is the cry. “You dishonor the flag of the nation that allows you to get rich on your talents, and you dishonor the military who died defending that flag and that freedom!”

Elsewhere I have explained that the flag does not represent the military; it represents us, as the citizens we all are, and the Republic we all are members of. And I have explained that Kaepernick is not opposing the flag; he is by his own words bringing light to the black experience in America at the hands of the police, an experience that is almost uniformly harsher, more brutal, and significantly more likely to result in horrendous physical assault and physical damage, up to and including death in some of the most innocuous of situations, from selling cigarettes or CDs on the street to holding a for-purchase gun that is for sale in a store to holding a toy gun in a park to arriving at a gas station for a fill-up to walking down the stairs in an apartment to…well, there are thousands of cases of black men and black women and black children being gunned down by police officers, far and above the rates of gun deaths by police of other Americans.

Saying that police are absurdly over-the-top brutal in their treatment of black Americans is not a point of dispute: actual data shows this, but actual data is ignored. We as white Americans listen to these reports when they infrequently come to our attention, dismiss them through rationalization stemming from our own protected experience, and think that black Americans are just too loud and touchy.

So Colin Kaepernick is attempting by his actions to highlight this situation in an environment where we are going to pay attention to him—as a quarterback and leader of his team, he is going to remain seated or kneel at a flag ceremony so that his actions will bring about reactions and re-examinations.

“A protest at a flag ceremony? How un-American and disloyal, how dishonoring of the flag and of our military!”

“Can’t you just do something else, quietly, in protest? We’ll support you if you do that. But don’t disrupt our ceremonies and don’t disturb our consciences” we ask.

Why protest when it causes us to be angry at protestors, especially (but not limited to) Kaepernick?

Well, maybe we should talk about protest…

The purpose of a protest is to (a) disrupt so that (b) the words/meaning can come out. By protest and disturbance the smoothly operating levers and wheels of life are halted, and people must step out of their ordinary experience into moments where they must grapple with what is happening, why it is happening, and what should be done to resolve the situation.

A protest that doesn’t disturb is more like a failed art installation. Pretty words and pictures that we look at and then move on.

A protest that halts commerce and entertainment is by nature disruptive but that is what a protest is for. To disrupt, to halt, to divert, to engage.

Black Americans have been speaking for centuries about their American experience through art, music, song, literature, speeches, sermons, illustrations, stories, and the like. All great methods to inform and connect. It’s pretty clear their American experience has largely been sub-equal. They have been treated more harshly and given far fewer places to express their American-given liberties. That is to our shame as Americans, but not shame enough to do positive things to correct it.

But black Americans (and others) also highlight their experiences and their calls for justice through protest, which gets us to stop treating their experiences and their cries for change as something culturally interesting but not all that important. Few people are changed by the experience of seeing a drawing about war, for example, but a nationwide, years-long protest over the Vietnam War finally convinced enough voters to put pressure on enough politicians that we ended that meaningless war.

Protests protest. They don’t accommodate, and they don’t play in the system.

Telling someone who’s protesting that it’s inconvenient to you and they should try again Tuesday is to miss the entire meaning of protest: it is not done to convenience you but to stir you up and make you start thinking.