When I watch a movie or attend a play or listen to music or read a book, I am usually present as the observer who analyzes my experience, always starting from “me” to say to myself “The author/creator is saying this and I either agree or disagree.” I remove myself one step from being in the moment. Sometimes, when I am experiencing a very good presentation I find myself “in the moment,” where I lose the sense of time and even self-awareness.

When I watch a movie or attend a play or listen to music or read a book, I am usually present as the observer who analyzes my experience, always starting from “me” to say to myself “The author/creator is saying this and I either agree or disagree.” I remove myself one step from being in the moment. Sometimes, when I am experiencing a very good presentation I find myself “in the moment,” where I lose the sense of time and even self-awareness.

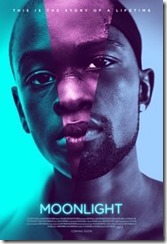

“Moonlight,” the movie directed by Barry Jenkins, and written by Barry Jenkins and Tarell Alvin McCraney, is neither of those. It is not a presentation where I was able to be one step removed, and it is not entertainment that enveloped me.

“Moonlight” is a movie of fewer words than you need in order to understand. It is the direct gaze and emotional journey of what it is to be in someone’s life without being that person. It is the closest thing to what life is, as if somehow by having a camera there to record a movie, which is, of course, written with a point of view and a direction in mind, we are there in the life of someone where there is no point and no direction. It is the sea we all swim in, where there is nothing from one moment to the next to guarantee anything, whether it is hate or fear or love or pleasure or hope.

There are three parts to the movie: “Little,” where we first see the main character, as played by Alex Hibbert, in his earliest youth; “Chiron,” now played by Ashton Sanders, where he comes into his own name; and “Black,” played by Trevante Rhodes, where he has become what he needed to be as well as what people wanted him to be—and even made him to be.

When you leave the theater, go back and look at the movie poster again. It will make sense.

I will attempt to post no spoilers. And I do not want to give away a single thing of this movie beyond that three-act arc.

I will just say—this movie chewed at my soul as the time slipped by, and at every step along the way we see humans wanting love and affection and even hope are given everything that destroys those hopes.

And yet, they continue. They want, they hope, they dream, and they are crushed. Still, they want.

Represented as a young man in a household where he is seen and not heard, the main character would join into the lives of others. But what happens instead (and that is the operative word here, in every circumstances) differs from what he hopes. As a boy on the cusp of becoming a man, the he has a single moment of connection. And as a fully grown man, he has adjusted his life to accommodate his pain in order to be at peace.

Several moments stick out, such as the response of his adoptive father (played by Mahershala Ali) at the table. Watch this, and hold onto it, for it will come in handy later when you recall this on the drive home. Another is in the middle scene, where the character becomes yet another mug shot for reasons entirely out of his control. And at the end, the muted man, using words that burn like acid, says at last what he wants.

I think there is such open rawness expressed here that does not come across as either heightened or softened. We are in these moments in our own lives, where we want to be seen and loved, and even touched. Watch for those moments in this film.

And watch for them in your own lives.

I am reminded of something written a hundred years earlier, by Edna St. Vincent Millay:

A Prayer to Persephone

Be to her, Persephone,

All the things I might not be:

Take her head upon your knee.

She that was so proud and wild,

Flippant, arrogant and free,

She that had no need of me,

Is a little lonely child

Lost in Hell,—Persephone,

Take her head upon your knee:

Say to her, “My dear, my dear,

It is not so dreadful here.”

One last thing, because of that one last thing: the final shot of the movie is all you need to know. No, not the final scene. That last, last glimpse into the person who would be seen and known and loved.

That is all we need, you know.

And that is, perhaps, all we need to know.a